UK AGENT

Mark Jefferies,

Yak UK Ltd,

Fullers Hill,

Lt Gransden Airfield,

Sandy, Beds SG19 3BP

+44 (0) 7785 538317 also see EXTRA AIRCRAFT UK

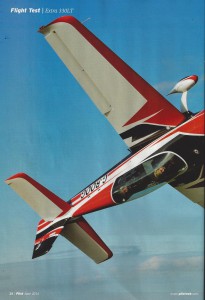

Flight test | Extra 330LT

Extra’s tourer

Adding speed and comfort to Extra’s popular two-seat aerobatic performer puts it into the Lamborghini league

Words Nick Bloom Pictures Keith Wilson

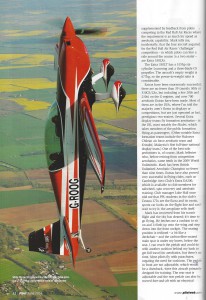

Anyone can drive a Bentley, but it takes skill – and willingness to put up with relative discomfort – to drive a Lamborghini. The Italian sports car says about you: “I value style and performance,” and, “I’m not just rich, I’m an exceptional driver”. Certificated aerobatic two-seaters have always had two markets: pilots who fly competitions and displays, and those who just want a sexy, high-performance aeroplane. The Extra 330LT is for the latter group; the ‘T’ is for ‘tourer’. (The L is for the low wing, to differentiate it from earlier models which had a wing half-way up the fuselage.) Of course, it is also for the serious aerobatic pilot who wants a faster, more comfortable journey between displays and/or competitions, especially if there’s a pretty (but demanding) blonde in the front seat. (And yes, the performer might be female and the blonde a male.)

I’ve been invited by Mark Jefferies, whose company Yak UK Ltd is the UK’s Extra agent, to sample an #Extra330LT, the first on the British register. The invitation came via cameraman Keith Wilson. “Sorry about the short notice,” he said, “but are you free tomorrow?” There is a tiny window of opportunity, between Mark’s flying the aircraft from the German factory to his base at Gransden, and his delivery flight to its new owner. It means flying it from the passenger seat as I’m not on the insurance, and, as Mark tells me after arriving in the aeroplane, “Not under any circumstances scratching the paint,” but this is one experience I’m not about to pass up.

Mark’s arrival is two hours late, a combination of headwinds and airport delays. However, it coincides with the last of a mild front blowing through and the clouds starting to clear. While we wait for blue sky I ask for Mark’s first impressions, seeing as he has 700-odd hours’ flying time in low-wing Extras. “It’s not that different,” he says. “The main change is to the wing section, which has gone from fully-symmetrical to semi-symmetrical. This is the result of design lessons from the Red Bull Air Races – how to make aerobatic aeroplanes faster.”

“So the LT is faster then,” I say.

“Definitely. It’s actually the fastest certificatd, normally aspirated piston aircraft in the world. Extra publish a normal cruise speed of 173kt. Maximum cruise is 205kt.”

“And does it feel faster?”

Mark considers. “I was too busy with the flat screens to give it much thought, but now you mention it, the control zones did seem to come at me rather faster than usual. And the acceleration at take-off was definitely quicker.”

I ask, but he hasn’t had a chance to see if the increased cruise speed has compromised aerobatic performance, “but we’ll have a go at that when we fly”. I suggest a pull up from maximum manoeuvering speed and counting the vertical rolls until there is only just enough speed at the top for a clean stall turn. “That should do it,” says Mark. “How many for Unlimited these days?” I ask. Mark says four. Apparently the roll rate is slightly lower in the LT, so it might be only good for Advanced contests. “And the handling in cruise – is that any different?” I ask. He considers again. “It had a more solid feel to it,” he says.

When Extras first appeared on the scene in the early 1980s, I was competing in a Pitts Special at Unlimited. The then two top-scoring UK pilots (a young Nigel Lamb and ‘Harpo’ – John Harper) acquired Extra 230s, getting sponsors and flying at airshows to help pay for them. A few years later, I entered an international Unlimited contest in Holland and came third in my group-owned Pitts S1S, largely because everyone else had switched to Extras and couldn’t quite get the hang of them. At every table in the airport cafe was a group of young men ‘hand-flying’ the smart new monoplanes they had parked outside. They were all searching for the holy grail, a good monoplane snap roll. As I recall you couldn’t simply go to full back stick and full rudder and hold them – you had to immediately reverse the elevator by just the right amount, to ‘unload’ the wing, otherwise the flick would ‘bury itself’… a whole new set of terms were developed to describe unsatisfactory flick rolls. (Competitors of that time might recall Roger Graham on the judging line jumping to his feet and shouting gleefully, “No flick, it’s a zero”). The trouble was that the Extra’s thick wing made it reluctant to stall.

Monoplanes were obviously harder to fly than the Pitts, but also a lot easier to judge and it was soon apparent that if you wanted to win, you had to have one. I and the two co-owners of the Pitts traded it in for the poor man’s equivalent to the Extra 230, a homebuilt (rather badly in our case) Laser. It was uncomfortable, primitive and difficult to fly. To avoid over-stressing the wooden wing, you could only fly aerobatics with twenty minutes of fuel. To get a negative flick roll required a karate kick one way and punching the stick forwards the other, and to do that meant sitting on the cockpit floor, which robbed you of all forward view when landing. Rolling circles could only be flown at one speed; a few knots faster or slower and the Laser fell out of the sky. The aeroplane was so twitchy that one pilot sideslipping on approach flew an un-commanded flick roll at 500ft.

Extra has changed monoplanes out of all recognition since those early days. Gone, the steel-tube empenage and heavy wooden wing, replaced by carbon-fibre composite in a structure that is stronger, lighter and has better aerodynamics. (It’s also, mind you, a lot more expensive to make.) Gone, too the mid-wing that made landing such a challenge because it cut out the view; when I first flew a low-wing Extra 330, I found it quite easy to land. (One of our Laser’s peculiarities was a tailwheel support so flimsy that you had to hold the tail up after landing, which did at least give you some kind of view.) Finally, although from the beginning Extras were always nicely finished, the ones you buy today are superbly painted with a surface like polished glass. Just look at the cockpit pictures and details like the grips on the control sticks and the design of the wheel spats – everything is made to the highest quality, no expense spared. The price of an Extra 330LT may be astronomical – in excess of a quarter of a million quid – but you get your money’s worth.

The flying qualities have been transformed thanks partly to feedback from competition and display pilots (including Walter Extra, who is one himself). In recent years, this has been supplemented by feedback from pilots competing in the Red Bull Air Races where the requirement is as much for speed as aerobatic capability. Mark tells me, incidentally, that the Red Bull Air Races is to have a beginners competition in which pilots can hire a ride round the course in a two-seater… and the three aircraft acquired for this are Extra 330s.

The Extra 330LT has a 315hp six-cylinder Lycoming and a three-blade CS propeller. The aircraft’s empty weight is 677kg, so the power-to-weight ratio is considerable.

Extras have been enormously successful; there are no fewer than 39 (mostly 300s or 330s, but including a few 200s and 230s) on the G-register, so likely several hundred two-seat Extras flying throughout the world. Most of them are probably in the USA where I’m told the majority don’t fly in displays or competitions, but are just operated as fast, prestigious two-seaters. Several Extra display teams fly formation aerobatics – notably the Blades, which takes members of the public formation flying as passengers – and there are any number of solo performers in Extras too. One of the best is, of course, Mark Jefferies, who tells me he’s paid far too much displaying his single-seat Extra at international displays as far afield as China to bother with the Red Bull Air Races. Extras have also proved very successful in flying clubs, such as Cambridge Aero Club’s Extra EA200, which is available to club members for tailwheel, spin recovery and aerobatic training. Club manager Luke Hall once told me that PPL students in the club’s Cessna 172s see the Extra and its exotic, sports-car looks on the flight line and can’t wait to try it; the aeroplane sells itself.

Mark has recovered from his transit flight and the sky has cleared; it’s time to go flying. He fetches me a cushion to sit on and I climb up onto the wing and step down into the front cockpit. The seating position is reclined – a bit like a deckchair – and the carbon-fibre-coated main spar is under my knees below the seat. I can reach the pedals, but could do with another cushion behind my back to get full travel for aerobatics, but there’s no time. Besides, a reclined contoured seat doesn’t really lend itself to additional cushions. The pedals in front are not adjustable, which would be a serious drawback, were this aircraft primarily designed for training. Nor are they adjustable for the rear seat; however, the rear seat can be slid backwards and forwards to compensate for tall pilots or the short-of-leg like me. The steel tube cockpit cage is evident around me and despite the luxurious finish and contour moulded composite seats, the cockpit is still rather spartan and workmanlike, were I – for instance – someone’s glamorous companion. (I can hear them now, protesting: “But there’s nowhere to put my handbag!”) I plug in and activate my noise-cancelling Sennheiser headset and strap myself in with the double Hooker harness and tighten the ratchets, Mark’s warning to, “Mind the bloody paint, Nick,” loud in my headphones. Mark starts up – a bass rumble from the front end – taxies out, lines up and then hands over control to me. He says to run up partial power on the brakes, release them and then ease up to full power, raise the tail, wait for 75kt, lift off and climb out at 90kt. I do all this and after a short run we’re up and away. The climb is brisk though far from startling and perhaps a little shallower in attitude than I remember for Extras. So far it’s all been quite easy, even from the front seat, which does rather reduce the view. Mark then takes control for joining formation with the cameraship and hands back to me for the non-aerobatic part of the air-to-air shoot.

As I orbit left then right, moving the aeroplane up, down, in and out in response to Keith Wilson’s hand signals, I continue to find this an easy, pleasant aeroplane. It’s obviously ideal for close formation work as the controls are powerful, but progressive, making it easy to fly smoothly (at least after the few minutes it takes for me to get the hang of it). At the same time, the response, both in engine power and pitch, roll and yaw, is immediate and I can feel the authority is there for fast, dramatic and sudden changes of position were I to need it. There is, though one exception, which is that the Extra is a little slower to decelerate when you are drawing ahead. Closing the throttle produces a series of staccato barks from the engine and does slow the aeroplane – a three-blade CS prop must have a powerful effect – but not that quickly. This is obviously a very clean and streamlined aircraft. Finally, the view of the cameraship from the front cockpit is quite superb.

As I say, I am enjoying myself and it’s with some reluctance that I hand back control to Mark for him to fly some formation loops, invert the aeroplane and approach for an upside-down shot and then fly some formation wingovers. The inverted bit does go on rather; I’m not used to hanging in the straps for so long and am just beginning to find it unpleasant when he rolls upright. However, the aeroplane does give you a fantastic view when upside down, perfect, again, for formation work. Mark graciously allows me to fly the head-on shot – a steep sideslip with the cameraship sideslipping the other way – and this is fun compared to other aircraft, because for once I’m not fighting a lot of inbuilt stability with shuddering leg muscles. Nor is aileron, rudder or engine going to run out of power, or the aeroplane stall and drop down. The control loading in this aircraft is wonderful, never heavy no matter what manoeuvre you are flying yet never over-sensitive and twitchy either.

Eventually Keith gives us the hand signal for ‘finished’ and the cameraship banks away. Back over Gransden and at a safe height, Mark hands control to me and I fly some basic aerobatics – a loop, four-point roll, stall turn, quarter-up, stall turn, quarter-down, an Immelman and some big, graceful Cuban combined looping and rolling figures. Nothing, in fact that I can’t fly in my Currie Super Wot, only in that 1936-designed, 90hp draggy machine, with an engine that cuts out under negative G, most of these figures are only just possible. Whereas in the Extra 330LT, they are almost ridiculously easy. The other difference is that in the Wot the figures are tiny, whereas in the Extra they are huge, big and graceful, using acres of sky. This makes these Extras spectacular at airshows, especially when fitted with smoke (an option for the LT). However, because the looping manoeuvres are so big, the G forces are sustained a lot longer, which does, to me at least, slightly detract from the enjoyment. I have just sat through some of Mark’s formation aerobatics, and am beginning to feel the effects: nausea and a slight headache.

Mark sits patiently through this rather amateurish display until I attempt an Avalanche – a loop with a flick roll at the top – that flicks, if it flicks at all, lazily enough to have been a barrel roll. (Blame those non-adjustable rudder pedals.) “Not like that,” he says and demonstrates a proper flick roll. I am amazed. “Do it again,” I say. He does it again. How can I describe a proper flick roll in this aeroplane? It begins upright and – bang – in an instant we’ve rotated upside down and back again, except that I have no perception of the actual manoeuvre. My mind simply can’t keep up with it, it’s so fast, literally as fast as the blink of an eye. “Do it again,” I say, for the third time and for the third time, Mark produces this amazing effect, something entirely new to me. “How’s it done?” I ask, remembering the Dutch airfield cafe with all those young men waving and twisting their hands. “Proper aerobatic pilots know,” says Mark a trifle smugly. Well I was one of those once, but as far as I’m concerned it’s a young man’s sport and I’ve outgrown it, so I don’t take offence.

Mark is curious about how the change of wing profile will affect the spin, so he flies a couple. To my mind the nose drop coincides with the rotation when it ought to come first. Also the rotation begins rather slowly, then speeds up, which might cause problems in Sportsman level competitions. Mark says, though, that this isn’t significantly different from other marks of Extra and dismisses my criticisms.

Earlier I pulled up to the vertical and pushed the stick over to the left. The Extra went through at least one vertical roll, maybe two, before I centred the stick, and then ruddered over in a stall turn. The roll rate, even from my relatively slow entry speed (well below maximum manoeuvering) was faster than my somewhat-out-of-practice perceptions so I became disorientated and lost count. Now Mark announces that he’s going to give the Extra 330LT the aerobatic performance test we discussed earlier: to see how many consecutive vertical rolls it will fly. When we opened the discussion, he suggested as the test a negative push to the vertical, followed by a positive snap roll and stall turn, but I vetoed that. “Remember I don’t fly much negative G these days. You wouldn’t want me to pass out, would you?” I said. Mark said we’d do the lesser test.

So now he’s doing it. He starts by really winding up the speed at full throttle in a shallow dive. He then pulls back firmly and the instant we hit the vertical, whams the stick over. We are perfectly vertical at zero G and sitting in the exact centre of the rotation so I don’t feel it. Unconsciously, I’ve been starting to close my eyes during the more violent aerobatics when Mark is flying them (but not during those flick rolls – there wasn’t time) and do so now, but I can hear Mark counting, “One, two, three…” and then I open my eyes. What I see is so disorientating and sick-making that I close them again: a nightmare-like whirling blur of colour which lives on as an after-image behind my eyelids. “…four,” I hear Mark say. I feel the rotation stop and open my eyes in time for the immaculate stall turn he produces.

“Do you mind if I take control? I’m feeling the effects a bit,” I say. Mark instantly gets the point and hands over. Then spoils the impression of sympathy. “Just remember that it’s a lot easier to wash a pullover than a cockpit,” he says, sternly. “If you must spew, do it in the front of your sweater.” I have a feeling he’s been here before.

With my hands on stick and throttle and my feet on the pedals again, the nausea backs off. Mindful of the need to get on with things – surely fuel must be running low by now – I manoeuver the aeroplane down and into a tight, curling circuit, joining downwind more or less over the hangars. The view is magnificent so long as I’m banking. However, when I level out on short final, in order to keep to the approach speed of 85kt, the nose must be high enough to blot out much of the view. (Mark says later it’s much better from the rear seat.) Having said that, the aeroplane is smooth and slides down the approach with enough stability that I feel safe and in control (and not just because I have Mark as a safety pilot). Some of his directions from the back seat begin to seem rather odd until he explains that his friend Claire has come out to take a photograph and he’d like this approach to be a fly-by. Mark takes back control for a mercifully short few seconds and then (possibly with the necessity of a vomit-free cockpit in mind) hands back to me. My second approach continues right down to the grass, without too much help from Mark and we touch down surprisingly softly on what is evidently a rather forgiving undercarriage (the legs flex and are fibreglass, not steel or aluminium) and roll down the runway. I’m a little early on the brakes and Mark reprimands me, but then he knows where the far end of the runway is – a long way off actually – and I’m blind from the front seat.

After landing I go into the clubhouse to recover and make a mug a tea. Claire is there. “What do you think of it?” she asks, her eyes shining. I’ve flown with Claire a few times in her and her husband’s Sky Ranger and I wouldn’t have thought she was the Extra type, but it turns out I couldn’t be more wrong. Encouraged by Mark, she had aerobatic lessons in the two-seat Extra he kept at Gransden and absolutely loved it. She ‘placed’ in her first aerobatics contest at Beginners level and that year came high up the scores in two more. I don’t ask why she stopped and it may have been the cost. However, like many other pilots I’ve met, I’m guessing that trying aerobatics and sampling a high performance machine like the Extra for a while was enough. After a year, she was content to go back to the relatively sedate pleasures of a slow, non-aerobatic microlight.

I’m still feeling out of sorts, but a walk in the fresh air sets me to rights and I go to join Mark and Keith at the aeroplane to remind them to photograph the luggage locker. This is truly an innovation, as the carriage of luggage of any kind has always been forbidden until now in Extras. You literally could only carry what you could put in your pocket. All these remarkable aerobatic monoplanes are fully certificated with EASA, the CAA and the FAA, and no doubt this was one of the requirements. Mark says having somewhere to stow clothes will be a boon. He had TNT deliver a tea chest with clothes and tools to the World Aerobatics Contest in which he competed in Spain, only to find that TNT refused to collect it afterwards because it was in a military air base. The locker is limited to 22lb and can only carry low density items like clothing, but it’s a lot better than nothing. Another ‘luxury’ is that the LT is fitted with an LED cluster landing light as an aid to touching down in poor visibility… and it has wingtip lights and strobes.

As befits a touring aeroplane the LT carries a lot of fuel, 9 litres in the acro tank (sufficient for seven minutes’ inverted flight), 60 litres in the centre tank in the fuselage and 76 litres per wing in wing tanks, making 221 litres in total. This gives a range of 562nm at 173kt. The cabin is fully heated (via the exhaust muffler) and there are very effective fresh air nozzles – I turned mine both to full on and directed them at my face as soon as I began to feel sick and they really helped. Although this is a taildragger, like most modern aerobatic aircraft, it will cope with quite strong crosswinds. And with powerful brakes and a 60kt stall speed it can land on short runways, I would say down to 500 metres or even less. (Take off distance to clear a 50ft obstacle is 385 metres.) The seats (well the front seat – I never did try the rear) are comfortable and the view out is pretty good for navigation, although with the sophisticated flat screen nav fit, that’s hardly needed. You would still, though, need some skill as a pilot to operate this aeroplane. Those rich enough to buy one as a tourer will earn the admiring looks it will bring them, even if they never fly a single roll or loop.

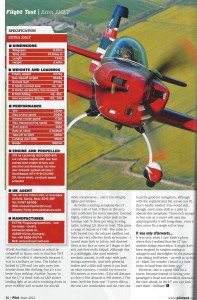

SPECIFICATION

EXTRA 330LT

DIMENSIONS

Wingspan 8.00m

Wing area 1084msq

Length 7.01m

Height 2.6m

WEIGHTS AND LOADINGS

Empty weight 677kg

MTOW normal 950kg

Load (normal) 273kg

Loading normal +6, -3G

Acro loading two on board MTOW 870kg, +8, -8G; single pilot MTOW 820kg, +10, -10G

PERFORMANCE

Stall speed 60kt

Cruise speed 173kt

Max level speed 205kt

Max manoeuvering speed 158kt

Vne 220kt

Rate of climb 2,104fpm

Take off to 15m 385m

Landing over 15m 350m

Range 562nm

ENGINE

Lycoming AEIO-580-B1A, 315 hp six-cylinder engine with two fuel pumps (one engine-driven, one electric) and Gomolzig, six-in-one exhaust system

PROPELLER

Muehlbauer, MTV 9-B-C/C198-25, 3-blade, constant speed

PANEL FIT

Aspen PFD and MFD, Garmin GNS 430W, XPDR Garmin GTX 33 Mode S, EI MVP-50P engine monitor, NAT AA83 intercom and (optional) ARTEX 406MHz ELT

UK AGENT

Mark Jefferies, Yak UK Ltd, Fullers Hill, Lt Gransden Airfield, Sandy, Beds SG19 3BP

+44 (0) 7785 538317 also see EXTRA AIRCRAFT UK

WhatsApp me

WhatsApp me

You must be logged in to post a comment.